August 12, 2025

During my recent bikepacking trip through the Dutch countryside, I had one of those sudden insights about how we actually use technology in our daily lives.

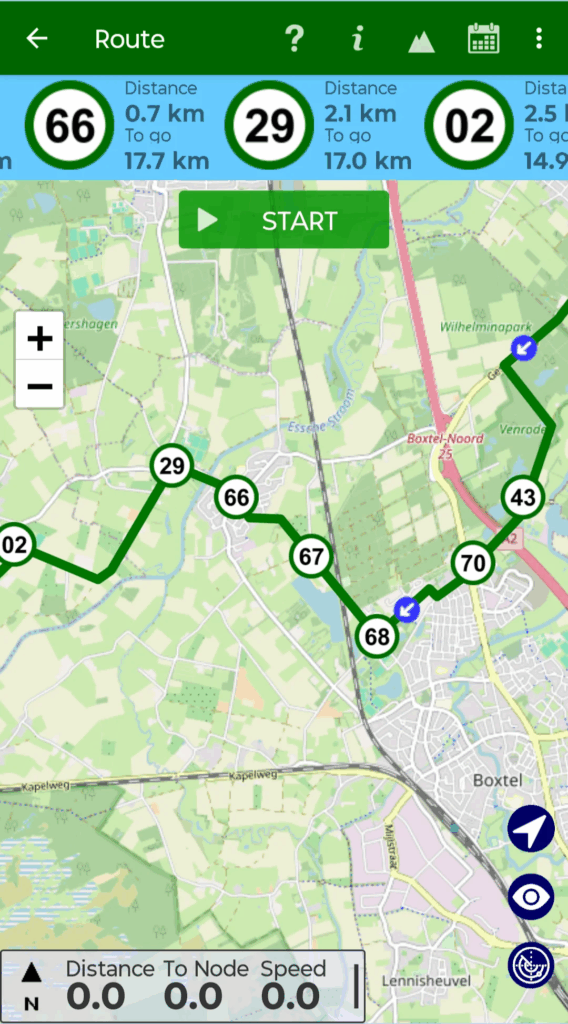

I’d planned my routes using the brilliant Fietsknoop – a sophisticated web app that navigates the Dutch cycling node network by calculating the shortest path between numbered waypoints along cyclist-friendly “green roads”.

The app creates a simple list of nodes forming the shortest path: start at 47, head to 23, then 89, then 12, and so on until you reach your destination.

The obvious next step seemed to be to mount my phone in the bike holder for turn-by-turn navigation. But after just one morning of cycling, this turned out to be a less than ideal setup. The screen became unreadable in bright sunlight. The battery drained faster than I expected. Every time I wanted to snap a photo or check something else, I had to fumble with removing the phone from its mount.

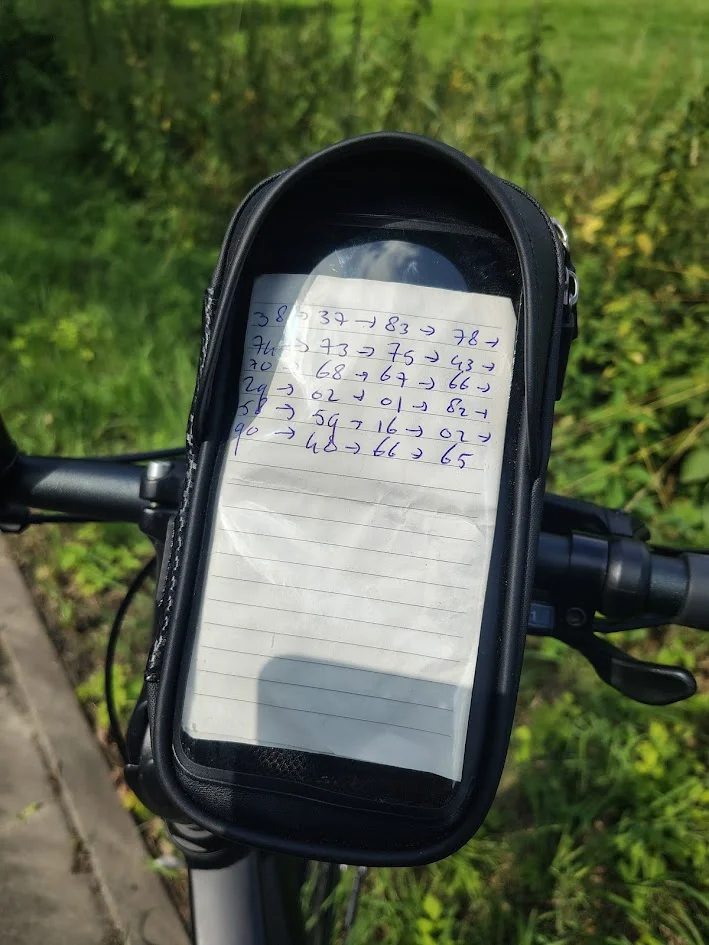

So I did something that felt almost not done in our hyper-connected online world: I grabbed a piece of paper, wrote down the sequence of nodes for the day’s route, and inserted it into the smartphone holder instead.

Suddenly, everything worked better. No fear of a dead battery. Perfect readability in any light. My phone stayed safely in my pocket, ready for taking photos and looking sights up. The simple paper list did exactly what I needed – nothing more, nothing less.

This on the road experience brought me back to Michael Gurstein’s work on “effective use” of information and communication technology. Gurstein argued that having access to technology isn’t the same as using it effectively. Effective use happens when technology genuinely improves outcomes for people and communities, not when we simply use the most advanced tool available.

My paper navigation slip was a great example of this principle. I’d used sophisticated digital route planning where it excelled – processing complex network data and optimization calculations. But for the execution phase, analog technology proved to be superior given the constraints of cycling: weather exposure, power limitations, and multitasking needs.

This connects to what E.F. Schumacher calls “appropriate technology”: the idea of matching tools and solutions to actual use contexts, rather than defaulting to whatever is newest or most feature-rich. The concept argues that sometimes the most effective solution means consciously choosing simpler or less advanced technology to better serve real practical needs and the local context, rather than merely pursuing technological progress for its own sake.

There’s also something here about what Susan Leigh Star and James R. Griesemer originally called “boundary objects”: things that bridge different domains effectively. My handwritten route list became a perfect boundary object in their sense, translating digital planning into a format optimized for physical navigation.

Furthermore, this resembles what Peter Pirolli and Stuart Card called “information foraging theory”: just like animals adapt their foraging to local conditions, we instinctively optimize information-seeking to minimize effort and maximize payoff. That piece of paper was a perfect solution: it imposed zero cognitive overhead while cycling, even with a smartphone full of mapping capabilities beckoning me from my pocket.

What this means in practice

- Context shapes everything: The right solution depends on your actual constraints and environment, not on what’s newest or most advanced.

- Hybrid approaches work: Use digital where it adds advantage, analog where it’s simpler or more robust—there’s no rule you must stick with one medium.

- Simple often wins under pressure: In challenging or unpredictable situations, straightforward solutions usually work better than complicated ones.

- Question your defaults: Just because you can use the high-tech solution doesn’t mean you should

- User agency matters: The most effective tool is often the one you tweak or adapt to fit your needs best.

Sometimes really less is more and the most innovative thing you can do is reach for a pencil and paper. Where in your own life could you benefit from mixing high-tech planning with low-tech execution (or maybe the other way around)? What advanced tools do you use because they’re supposedly better, rather than because they actually work better for your specific situation?